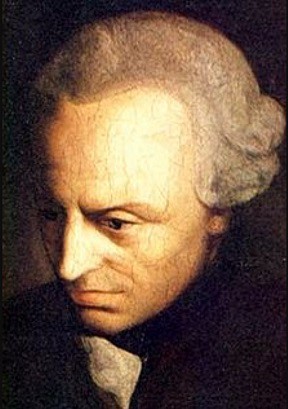

Immanuel Kant was one of the leading philosophers of the 18th to early 19th Century. His philosophy has influenced both national and international law while reflecting many of the common philosophical notions from his time. Some of those ideas he explored were social contract theory, ethics, and rights. Specifically, as pertaining to rights, Kant delved into the concepts of citizenship and voting rights, known as suffrage. He maintained an Aristotelean hierarchical scale of persons, and that there were qualifications one must meet in order to be a citizen and to be able to vote. A background in his philosophy, as well as refutations in regards to his stance on citizenship and suffrage will be provided, respectively. It is my position that Kant was incorrect in asserting unjustified limitations on citizenship and voting rights.

Kant postulated a hypothetical social contract theory, as opposed to a historical social contract theory, and this delegates the burden of proof to an a priori non-entity, namely Kant’s own philosophy. A reader is to only assume Kant’s proposition as being correct, and not worry about the details of how a state came to be, whether it is a justified state, how property owners came to own property in the beginning, or whether the powers in charge are themselves justified, etc. In part, this is because Kant did not think it appropriate to question authority or fight against unjust leaders, as he held to claim authority is to claim the right to be obeyed. This leaves an unrealistic amount of open-ended power in the hands of those in charge with a naïvely optimistic outlook in an idealistic utopia that leaders will conduct their duties justly.

Kant believed only property-owning male active members of society could be citizens of the state, and they were the only ones who could vote. With that in mind along with his hypothetical social contract theory, it is farfetched to maintain a just state. This is especially true when the victims of the system, e.g. women, youth, the poor, minorities, etc. have no say through voting, about what happens to them or their potential futures. Kant’s system is predisposed to keep the wealthy independent and rich, and to keep the rest of society voiceless and dependent.

Kant held three key theoretical deductive, a priori, principles to be true of all people. The first of which was that of ‘freedom.’ He believed that all properly functioning men’s wills are naturally free to act in accordance with pure reason. For Kant, ‘reason’ is only concerned with a priori concepts and not rooted in sense perception; while ‘understanding’ is based on a posteriori evidence, or axiomatic sense experiences. So, no matter what new evidence may be brought to someone’s attention in regard to limitations of one’s will or a lack of freedom as pertaining to their will, Kant would suggest they are still free by their very nature of possessing a will as being a person (91).

While I agree that people have a free will to act, moreover all people have the ability to actually choose; still, our experiences, surroundings, situations, choice limitations, etc. nevertheless affect our decisions and help us as rational people make reasonable decisions. Kant’s philosophy is that of a duty-centered approach, or deontological. Within deontological ethics, specifically with Kantian ethics, one ought not choose things based on end results. This is the limitation of his approach to a free will versus freedom of choice. Where a free will is the capability of acting in the present moment, a free choice is in search of an end result. To neglect the first is to neglect personal responsibility; to neglect the latter is to neglect logic. Such as it is, I disagree with Kant’s definitions of ‘reason’ and ‘understanding.’

Kant’s a priori principle of ‘freedom’ is translated to his essential rights to citizenship as lawful, or juridical, freedom. Those men with property had the freedom to act in state matters as well as in society, according to Kant. This was essential to being fit to vote, as the independent property-owning men were the ones that were to be taxed in order to help the less fortunate and the dependent society in general, and were the ones with something significant to lose. He claimed that men without property could potentially work their way up in the world and own something, making them fit to vote once they accomplished that task. Nevertheless, Kant specified being fit to vote was essential to be qualified for citizenship (91).

I disagree with Kant’s incessant position of societal hierarchies as it pertains to limitations of being qualified for citizenship, essential rights to citizenship, and specifically to voting. I can understand Kant’s argument that independent property owners have the most to lose, but a state’s laws affect far more than property. If people are, indeed, all born to possess a free will, and the general will of society is to establish a state of justice, free wills are not to be subjugated by others through a coercive state as that would be an injustice. To deny a voice through voting for those that are to be affected by certain laws is to dogmatize the state and subjugate those persons harmed. Equal voting rights are critical in providing a voice for women, minorities, and the otherwise voiceless. Additionally, by not even allowing property-less men to vote, the state has greater potential of harming them and preventing them from becoming property owners, citizens, and being fit to vote, as Kant would have it. Kant’s system establishes an oligarchy keeping certain people in power, i.e. property-owning men (34).

The second a priori universal principle he claimed was that of ‘equality.’ Kant believed that all people are born equal in a state of nature, and remain equal in nature. This was, once more, specified as an equality of the will, and all people have the ability to act in accordance with reason. When put into terms of essentials to citizenship, it would be ‘civil equality.’ This concept of equality is that all men have the equal opportunity to become citizens, thus an equality to vote. This equality was not extended to, as previously mentioned, women or those without property. Those passive associates of the state had equality among themselves, as being beneficiaries of living in a state that provides for their lacking. Therefore, the state has the authority to make fiduciary declarations on their behalf, whether it benefits or harms them, treating them as underlings to the wealthy men (91).

I disagree with Kant’s idea of ‘equality’ as a division of classes and then declaring everyone as being equal, or having equality, especially as it comes to equality under the law. Equality under the law is vital for a system of justice to prevent wavering subjectivity in a legal society. Just as a person has a natural right to speak for themselves, so too does one have the right to speak on their own behalf when others are to decide what happens to this person. Votes do have the potential, and ability, to remove certain rights and privileges from people. If a thief proposed the question of whether their potential victim wanted to be robbed or not, the potential victim would probably say they did not want to be robbed. This also goes for a state that has voting, where citizens need the ability to voice their opinion and have the ability to vote while not merely kowtowing to the upper echelon with every passing vote (92).

Kant’s third a priori principle is that of ‘civil independence.’ This is the respect of persons while maintaining one’s own personhood. He affixes this to civil independence under rights essential to citizenship. This is closely related to his fourth citizenship essential of ‘civil personality,’ which calls into question ‘personhood’ versus ‘humanhood.’ This means that one is a human by their very nature, but may lack the capacity, or actuality, of being reasonable at that given time. For example, a baby is a ‘human,’ but not a ‘person’ because it cannot reason on its own and it requires a fully functioning person to assist it. However, the baby has the potential of becoming a person one day, just as Kant said men without property had the potential of one day owning property and becoming active members of the state. This is not to say that Kant suggested men without property were not ‘people’ with personhood, but he does show similar treatment of their being within the state (91).

His argument is that these humans are unfit to vote because they lack the capacity to reason having no will of their own. Other examples of not having personhood are the mentally ill and the elderly unable to function. This presupposition of being their own masters, according to Kant, is crucial for qualifying one for citizenship. When married, a woman’s property became the husband’s, and they were to rely fully on their husband. This suffices to say, Kant did not think married women could be active members of a state or citizens, as he would have that they are rationally and morally inept by their nature of being female.

On one hand, I agree that there are limits to humanhood and personhood, e.g. babies should not be permitted to ‘vote.’ On the other hand, for a just system there needs to be a better determinant of how a ‘person’ is defined, especially concerning suffrage. To even allot a state to capriciously determine such is a travesty in its own right. When a Kantian system is operated by a single class of men, as it is typical to vote in favor of what will benefit them alone, this leaves those passive associates of the state subject to the whims of those in power. This type of system is not just, and in a state of nature behaviors like these could easily lead to a usurpation by those currently suppressed. It behooves a society to declare a simple answer to what is personhood, and to then realize inconsistencies will typically handle themselves as related to voting. A single vote has a minuscule chance of changing anything, and keeping the masses happy with voting their idiosyncratic ways keeps a state together. Viz. I disagree with Kant’s deontological, or duty-centered, approach to civil matters. Once people begin determining who is in and who is out, it becomes an ongoing scheme. Rather, I take a teleological position, or results based, and envision better results from allowing even the dim-witted to vote.

Throughout his philosophical system of determining qualifications one must possess in order to become a citizen, what rights are essential to citizenship, and who may vote, Kant put himself into a ‘natural dialectic,’ which is indulging into arguments that contradict and undermine one’s own philosophy. In a roundabout way, Kant preposterously conveyed that mankind was and is born with freedom and then they decided, because of voluntarily joining society and forming a state, they spontaneously wanted to throw away their natural right of freedom. They were once equal, but because they wanted to join in a protected society, they needed to discard that equality for their unified benefit. They once had their own independent being that mattered most, but because a state requires a unification of autonomous wills, it was incumbent to define ‘personhood’ and determine that those in power know what is best. Finally, those that had nothing, or women, agreed to accept the dictum that they should not have a right to vote or to speak against the newly established authority.

Overall, Immanuel Kant claimed ‘freedom,’ ‘equality,’ and ‘civil independence,’ to be a part of people by their nature of being persons with capabilities to reason. He had no qualms eradicating those concepts when it came to establishing a state, so long as his hypothesized utopia lived by the definitions he provided for those abstractions. Kant expounded that people were moral for simply carrying out their moral duties, not questioning authority, and not being motivated by end results. In regards to voting, it is evident that those prevented to vote were to not question or concern themselves with whatever results may occur. They were to trust in the omnibenevolent Kantian system of duties.

Works Cited

Kant, Immanuel. Kant: The Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge, 2012.