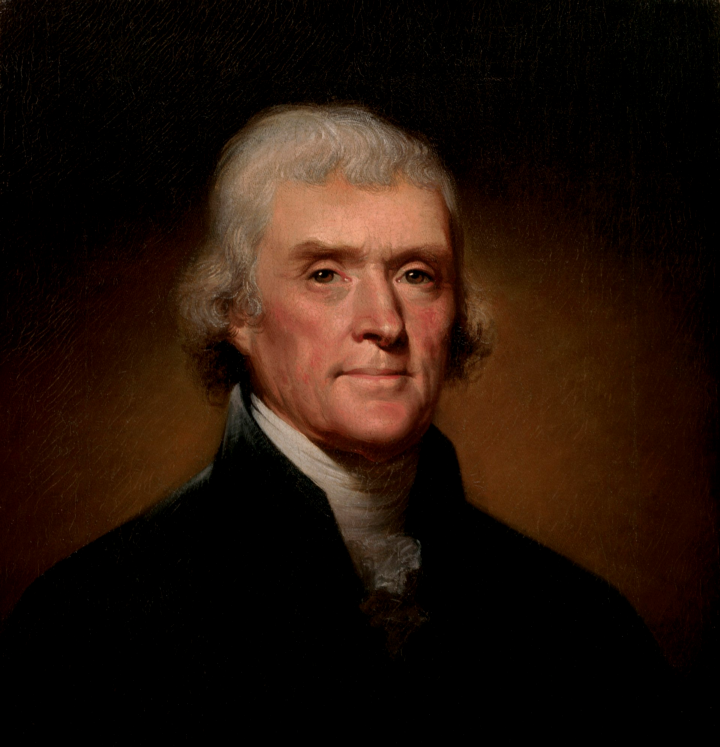

Painting of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800.

Thomas Jefferson: April 13, 1743 — July 4, 1826.

Thomas Jefferson was not only one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, but he was also the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, one of the framers of the U.S. Constitution, and the third President of the U.S. His legacy lives on as one of the most significant contributors of the American Revolution era. Jefferson’s political views have many of their roots in the philosophy of Natural Law, and it is from ‘Natural Law’ philosophy that ‘Natural Rights’ arise. Throughout his writings, the concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘Natural Rights’ can be found, leaving some readers confused as to how these abstractions may be contradictory as especially pertaining to slavery, political inequality, and exclusion. This essay will introduce Natural Rights and Jefferson’s perspective of these rights, clarify some of the perceived misunderstandings as they relate to slavery, political inequality and exclusion, and explain my contentions with his use of Natural Rights.

Natural Law is a philosophy that stipulates certain unalienable rights, or ‘Natural Rights,’ arise from one being a person capable of reasoning, and some philosophers have said it was because people are from God. Each person has property in themselves and are responsible for their work and actions. When in interaction with other people, these Natural Rights suggest that each individual person is to be free from external restraints from others; this freedom is known as “Negative Liberty.” This philosophy shaped many of the ideas held by Thomas Jefferson through the works of various philosophers such as Algernon Sidney, Adam Smith, and more notably, John Locke. The philosopher John Locke declared that people are to be “free” in the ‘Negative Liberty’ sense of the word, in their own “Life, Liberty, and Property.”

It was that specific wording that influenced Jefferson’s wording of the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

These Natural Rights that Jefferson held to be self-evident were to be for all people. This idea of being free from the coercion or force by others is what he argued for against the British who, as he properly saw at that time, as enslaving America to the arbitrary will of the king of Great Britain and Ireland, George III. Throughout his life he would be a self-proclaimed abolitionist, for the emancipation of African slaves in America. As early as 1769, Jefferson, as a young member of his Virginian county government, requested the emancipation of slaves but was denied (9). In 1778, he successfully drafted a bill to end the importation of slaves into his state of Virginia (237). Jefferson desired the freedom of slaves to come about in a democratic manner, rather than a government declaring what should be done without the support of the majority of citizens.

As perplexing as it is, Jefferson owned slaves and did not relinquish them on his own, although he claimed that citizens should be the ones to voluntarily decide to abolish slavery. In part, this is because he did not see Africans as equal persons to Whites, he saw Africans, or blacks, as inferior to all others as it came to mental capacity (238–241). So, for Jefferson, it was easier to excuse chattel slavery as he did not see African slaves as being equal “persons,” but merely “human” by their nature. One is “human” simply by their virtue of being a part of the species Homo Sapien, while being a “person” dictates that one is a fully conscious, rational, functioning, being. Additionally, Jefferson was concerned about the future of the nation if slaves were freed. He was worried that they would not be fit for much good, and that they may mix with Whites, so for their own benefit he believed they may be best suited for slavery (243–244). In fact, this line of reasoning comes from Aristotle’s philosophy of ‘Natural Slavery,’ which is that some people are born to be slaves by their very nature.

Jefferson’s perspective of the natural inequality and political inequality of various groups, such as white men compared to blacks and natives, or even to women, would be visible across his political career (239–240). With his political party known as the Democratic-Republican Party running in opposition of Hamilton’s Federalist Party in the late 18th to early 19th Centuries, Jeffersonian democracy would eventually come to make all white men equal with one another and allotting them the rights of suffrage regardless of status. Although this movement spoke out against aristocracy and the requirement of owning property in order to vote, the right to vote would not be granted to women, natives, or blacks (246). Moreover, Jefferson’s position of the right of white men to vote, and not others, was because he saw that they were the ones capable of fighting for the nation on their own accord, and were willing and able to pay taxes (221).

These perceived natural inequalities, held by Jefferson, permitted exclusions in society and within the state. In society it perpetuated the cultural standard of the subjugation of blacks, natives, and women as all being less than white men. This continued the problem of blacks being less educated because everyone was led to believe there was no hope for the majority of blacks having even the capability of becoming learned (243). For natives, it prolonged the societal idea that they were solely savages and barbarians. For women, it maintained that they and whatever they possessed was to become a man’s property, for they were treated as the de jure property of their husband, and in society it behooved them to marry as women that did not were looked down upon. Equally, these three groups were, for the vast majority of the time, kept out of the political world and prevented from voting or voicing their opinions.

Jefferson’s mistake of applying a democratic process to Natural Law, thusly Natural Rights, is what steered the philosophy into an ongoing servitude of blacks, natives, and women. These Natural Rights are a priori and a part of Moral Realism, also known as “Moral Objectivism.” That is to say, there are moral values and facts that exist whether or not one person or all of society realizes it. The philosophy of Natural Rights is best suited in the political world to not make determinations such as what constitutes as an adult person, who is equal or not equal, or who is better equipped to speak, etc. The place of government was to establish justice, in the negative sense, as a separation of peoples who voluntarily exchange goods and services. That government is to protect the people within that state as it pertains to their Life, Liberty, and Property. This protection is for all “humans” and “people,” alike, as being equal under the law. This equality under the law was to create harmony and balance with Justice being blind no matter the race, creed, sex, religion, financial wherewithal, status, or cognitive capacity, etc.

If only Jefferson did more to search for the commonalities between people rather than their differences, he could have potentially maintained the philosophy of Natural Rights within the U.S. government, recognizing that we are all equal under God and by our nature of being human. This equality would have encouraged a freer and more prosperous society not only for white men, but also for blacks, natives, and women, preventing some of the problems to come after his time. Nevertheless, I am grateful for some of the things accomplished by Jefferson, and some of his philosophical views aside from the aforementioned. If it were not for the philosophy of Natural Law, Natural Rights, Thomas Jefferson, and people like him who helped to found our nation, we may not have had a United States of America.

Works Cited

Jefferson, Thomas, et al. The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Modern Library, 2004.